‘If You Lie, You’re Compromised Forever.’ How Russia’s Largest Tech Company Collaborated With the Kremlin Long Before This War

An interview with Lev Gershenzon, the former news head for Yandex, Russia’s most-visited web site.

Tuesday, March 1, was the sixth day of Russia’s war on Ukraine.

People across the world shuddered at the unbearable headlines: Missiles struck Kyiv’s TV tower, killing a passing family. A residential neighborhood in Kharkiv was devastated by apparent cluster munitions. In an emotional address to the European parliament from his besieged capital, President Zelensky said that sixteen children had been killed.

But that’s not what millions of Russians were reading on the homepage of Yandex, the country’s main web portal.

The headlines there bordered on the soporific: China supported dialogue. Biden said there was no threat of atomic war. Putin signed a series of economic measures against the United States.

Lev Gershenzon, the onetime head of the Yandex news division, couldn’t take it anymore. In an impassioned appeal to his former colleagues on Facebook, he begged them to drop the site’s filter, which allows only pro-government news sources to come through.

“Today is the sixth day that, on the main page of Yandex, at least 30 million Russian users are seeing that there is no war,” he wrote. “It’s not too late to stop being accomplices to a terrible crime.”

At a time when so few prominent Russians were speaking out, I was struck by Gershenzon’s candor, translated his post into English, and posted it on Twitter.

I thought that would be the end of it, but I couldn’t stop thinking about him. What had moved him to write it? What was it like working at Yandex? How did he weigh the company’s moral responsibility for the war? So I reached out to him to hear more.

The Moscow-born Gershenzon holds a master’s degree in theoretical and applied linguistics. By profession he’s a product manager with a focus on natural language processing — a perfect fit to run an advanced news aggregator, which he did at Yandex for about five years. After leaving in 2012, he founded Detectum, an e-commerce search service he now runs from Berlin.

We spoke for almost two hours, so only a portion of our conversation, which I’ve translated into English and edited for clarity, appears here.

Among the topics we covered:

How the Yandex “news filter” works.

Why the company started “making compromises” with the Russian presidential administration as early as 2008, and why those choices matter today.

What moral responsibility Russian tech companies — and really, all tech companies — have toward their users.

Painful as they can be to watch, why U.S. Senate hearings can hold such fascination for foreigners.

What the future holds for the Russian IT sector.

How secret compromises with the government can turn into something much worse.

For all of this and more, read on.

Lev: There’s one thing I want to say, and then I'll shut up. It was very unexpected, the huge reach of your tweet. This past week, all I've been doing is talking to journalists and giving interviews. I've started refusing, but of course I couldn't say no to you.

Ilya: Thanks, I'm very glad.

I mean it, thank you very much. And this crazy level of interest, I think, is because Western journalists, and even a lot of people in Russia, can't imagine this ‘filter’ mechanism I described.

There are tens of millions of people in Russia who use Yandex — but they simply don't know. They just don't know.

How does this ‘filter’ work?

The main Yandex page has a news section. These five headlines.

This isn’t what people come to Yandex for. People come for the traffic information, for the weather, to buy something, to look at maps, to order some groceries. But they always get this too.

These are what we call stories. And if you click on a headline, you get more about the same story, from different sources.

Roughly speaking — I don't know the numbers because I haven't worked at Yandex for 10 years — this page has 30-40 million views per day.

And this is curated? It's done manually?

No, look: It’s like Google News. The topics get clustered and annotated, and the snippets shown, totally automatically.

But here’s the trick: There's a filter. There are only about 15 news sources whose headlines can be displayed. Look, we can count them.

Rossiyskaya Gazeta, Lenta, Tass, that’s three. RBK, Interfax, that’s five. Gazeta, six. Sport Express. Is that a joke? Seven. RIA Novosti, eight. Vedomosti, nine.

So look, out of 15 headlines, we counted nine outlets. For a service that has thousands of sources. Isn't that strange? You can see them repeating. Three from Lenta. Two from RBK.

When I was at Yandex [until 2012], this list had maybe 50. We had an agreement with the presidential administration. They were saying: “The main page has such a large audience, and it needs to show only the most reliable sources.”

I said, guys, we have algorithms. But we agreed that it would show only “official” outlets that have media licenses. This list was 50 or 60, pretty long. That was an unpleasant compromise. That’s why compromises are dangerous. They lead to what's happening now.

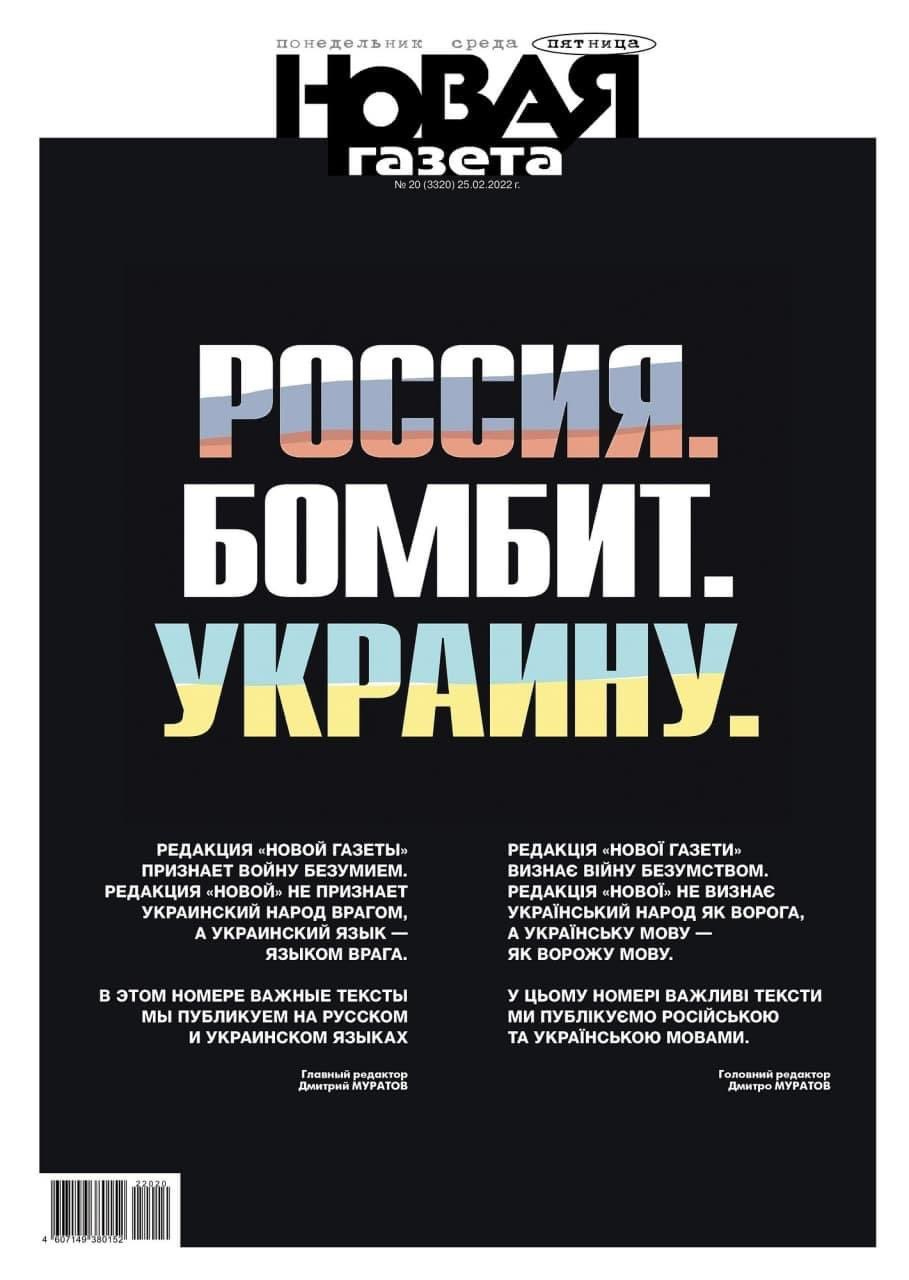

And [the independent newspaper] Novaya Gazeta will never be on there.

Exactly, exactly.

You were saying that compromises are dangerous. And some of the compromises were made years ago. Even before this war — say, five years ago — it already would not have shown anything from Novaya Gazeta.

Five years ago, no. When I was at Yandex, it was still there, because we agreed the list would include licensed, official outlets. But in those ten years, a lot of things happened.

[Lev lists Russian outlets that have lost their independence.]

When I was leaving Yandex, Lenta.ru was still Lenta.ru, Gazeta.ru was there. It was different. Kommersant and Vedomosti were there.

But here's what I'm trying to say. This filter of 10-15 sources is not regulated by any legislation. It's just a result of shadowy, non-public agreements between Yandex and I-don't-know-who. In my time it was the presidential administration. Now it might be some lieutenant colonel from the FSB. Doesn’t matter who.

In the last few days, about 20 outlets have closed or have been blocked. But when I was writing my Facebook post, they were still functioning and not even blocked yet.

So when I was writing, I was saying, guys, every hour is critical. First of all, I meant that people are dying every hour. And also, every hour, people are being misinformed. Yandex and other media companies — but Yandex is the biggest — are participating in that. And I still had people there who I personally know, so I addressed them.

Yandex thought about it, discussed it, and of course decided not to do anything. Meanwhile, they passed this “15 years for fakes” law in three readings.

[New legislation, swiftly passed after the war, made publishing ‘false’ information about the war — even calling it a “war” — punishable by up to 15 years in prison.]

So now it's too late.

That's why I'm not talking about it anymore. That's it. The train has left.

I hope you noticed, my post was very mellow. I didn't accuse anyone. I didn't say “you're blood-soaked traitors.” I said, guys, you’ve become accomplices. I'm giving you the chance, in case you haven't noticed, or didn't see it this way, to do something about it. Ideally, fix it. For half a day, great. For two hours, good. For an hour, that's good too. Even half an hour makes a difference.

Half an hour could mean a million visitors. That’s a lot of screenshots. And there's no law that forbids Novaya Gazeta from being on the main page of Yandex.

Because the filter you were talking about, it’s not because of a law. It’s just an informal agreement.

Yes, yes. There's no law that would ban Novaya Gazeta — it's not a “foreign agent,” it's not an “undesirable organization.” It's a licensed media outlet. I mean, their editor-in-chief just won the Nobel Prize. It’s not some random bullshit.

So I said, fix it if you can. If you can't fix it, make it look like it was hacked. If you can't do that, take it down. And if you can't do any of that, at least rip off your epaulets.

I said, I'm not labeling you. But it’s not just propaganda, like, ugh, that smells bad. It's complicity in war crimes!

And what were the reactions? I saw there was a woman who left.

Tonya Samsonova, yes. She's in London. She sold her project to Yandex, she cashed out, she worked there for a while. It's funny, I was talking to her today, and I was saying, Tonya, you did great.

But you know what kind of comments I got? “There he is, in warm, safe Berlin, telling us what to do. And we're here.”

How do you respond to that criticism, that it's easy for you to talk, from Berlin? But if you're in Moscow, you have a family, you have a salary...

Well, first off, I would say this. The correctness or incorrectness of my statements doesn't depend on where I'm located. I'm stating a fact. I'm saying, this news section is a cause, and the basis, of a criminal war that's been going on for two weeks.

That's a fact, right? I'm saying, do something about it.

If you don't agree with me, you can say that. Someone who's really seriously in denial can say, no, it’s not true. There aren't many left like that. But if you acknowledge that, then it’s your decision what you do with it. You can say, I'm a coward, or we can't fix it, or whatever. You can say, “I have a family,” or “I have a mortgage, so I’ll keep helping them bomb Kharkiv or Mariupol.”

There's another thing I can say. I have very close ties with Russia. I had a ticket for Moscow on March 15. My mom is there, my sister is there, I have colleagues there, and my son was there before he was able to get to Yerevan, thank God.

I have a history of being detained for taking part in anti-war protests. I posted on Facebook a photo of myself being detained eight years ago. On this point I'm pretty consistent. I worked in the news for five years, until 2012. One of the reasons I left — not the only reason, but one of the reasons — was because there were more and more of these compromises. I spoke out about that pretty clearly.

So, about these long-ago compromises. Right now in Russia, it's very dangerous to voice your opposition to the government. But it wasn't always. Ten years ago it wasn't as dangerous. Fifteen years ago, even more so. In my view, it's not that easy to blame Russians for not protesting now. But they have some responsibility for letting Putin, over the last 22 years, bring the country to this point. What do you think?

Yes. I would only add that "Russians" is a very large group. But "Yandex employees" is a relatively small group.

Yandex has created this image of a company that’s distanced from the Kremlin. But it's clear that they had very tight connections, and in the 10 years since I left, they became even tighter.

People tell me: “You don't understand. Those people are hostages.” But, man, you should see these hostages. They fly business class. They don't look bad for hostages. And the trade-offs. Those compromises we were talking about. Plus, I can only guess how much data Yandex shares with the special services.

There I can only guess, I don't know. But on the news part, I don't need to guess. I can see it, and anyone can see it. And that trade-off makes this argument about "hostages" pretty weak. Because they were there from the beginning.

Eight years ago, when Russia annexed Crimea, [Yandex CEO Arkady] Volozh had a choice. In my view, the right decision would have been to freeze, or to cut loose, everything that's happening in Russia, and to maximally invest in breakthrough technologies, and go into Western markets.

But they made a different decision. They decided to suck everything they could out of Russia.

Then they went a little bit into self-driving cars in the United States, and got some [delivery] rovers onto college campuses, and started to deliver food in London.

But they bought a plot of land for $150 million on Kosygin Street in Moscow, and for another $300 million they started building a headquarters there. So they put half a billion into an office. On the one hand, Google and Apple and Microsoft all do that. But on the other hand, this office is in Moscow. In Russia.

For me what's interesting now, is how to formulate these principles so that, in the future — in the world, in Europe, in America, everywhere — we’ll notice such things in 2014 or 2015, and not in 2022.

These informal agreements. A public company that's listed on the stock exchange can't allow itself to do that. That's the first sign. A red light should go on.

Did a red light go on for you, when you were there?

It did. But maybe not brightly enough. But now I think, in hindsight... I became very uncomfortable. I fought as hard as I could. There were two incidents.

One, we had an English news product, news.yandex.com. I really wanted to do that. I said, let's enter the U.S. market through this. And they got scared, and said “screw it.”

But here’s where a red light went on. [The Yandex executives] and I were talking. They said, we went to the presidential administration. We went and reached an agreement with [First Deputy Head Vladislav] Surkov. We agreed that, if there's a war, [Yandex] will go to manual control. And we’ll have a list of 15 [allowed sources], instead of 50.

I said, what do you mean you agreed? How will you know that there's a war? Who's going to call whom?

Wait, you didn't go to those meetings yourself? Weren't you in charge of the news product?

Exactly. That's a whole thing. I said, guys, why are you making agreements about my service without me? You agreed to something, and now you're just telling me about it?

The person who's responsible for the service should be able to speak the truth about how it works. And we did. We explained about the filter. We said, it’s 50 sources, with licenses in the country of publication, sorted by our citation index. And that's how it really was.

But this thing, about a “short list” during wartime. I said, okay, you agreed without me, you’re the managers, maybe you know better. Now tell me, who will determine that it's a war? I read the constitution. The president declares it, the Duma ratifies it, you mean in that case?

They said, no, come on, it has to be fast. I said, what do you mean fast? When Surkov says it? Surkov's going to tell you that it's a war?

So it was Surkov who curated you guys? Was there a specific point when it began?

Yes, Surkov. It began in 2008, with the war in Georgia.

Were they reacting to something specific? Was something appearing that they didn’t like?

Yeah. The starting point was, they came with a print-out of the news, and there were some Georgian sources. They said, what are you doing? Those are enemies.

We said, look, according to our algorithm, there's a story about Georgia. The Georgian sources have a high level of citation. So we’re displaying them. That’s good, that’s the point of the news. It’s an aggregator.

That’s when it started. It wasn't that we immediately started doing whatever they said. But [we decided] that a representative of the government is a representative of an important newsmaker. So we'll start explaining to them what we're doing.

My deputy then, Tanya Isaeva — later my replacement — she got a special phone. They had that phone number, and sometimes they called her.

Another case. It was funny. They released this [plan for the development of Russia] called “Strategy 2020” in 2008 or 2009. And sent it out to various outlets, and made everyone print it.

So everyone printed it, but the story didn’t appear on our site in the top 5. They were hoping it would be on top. They said, “what's going on? Everyone wrote about this!”

We started looking into it, and it was true, everyone printed it, but no one added their own text. So our algorithm combined it into one — it thought, there's the same text in various places. Duplicates don’t add to the weight.

Like a spam filter!

That's right.

It’s incredible. I'm getting the impression that they really, every day, looked at your page, and if they didn’t like something, they picked up the phone and called you.

Yes, that's how it was. This guy Kostin was horribly rude. Konstantin Kostin. He was with Surkov. He was curating the media. He's an idiot. He came to some meeting at Yandex, and he said, Google launched this cool thing, if you send an email and you're drunk, later you can take it back. It’s really cool, really convenient, ‘cause sometimes you get drunk. That's the kind of people they are, coming on black BMWs with their flashing lights.

How often did they contact you?

Maybe once every two weeks, I don't know. He'd write, "what is this?" We wrote, Konstantin, we'll figure it out right now. In a few hours, we'd write a detailed report, with numbers, with screenshots...

So it wasn't like a negotiation. They essentially gave orders, and you reported to them.

Exactly! That was the idea. I said, let's do it like this: They ask, we answer. But it's clear, rhetorically, that, when you ask "what the hell?" you're not expecting an answer.

When they asked “why do you have this,” they don't really want to know why. They want it not to be.

So I want the [tech] community to formulate it better. There shouldn't be any non-public agreements that you can't talk about.

If there's a law, then follow the law. But if there's no law, then there shouldn't be anything hidden.

Yes. Or, if you read that Facebook post by [Yandex Executive Director] Tigran [ Khudaverdyan], it's very hypocritical. You can show it to children at school, to have them find manipulations, factual errors, exaggerations. It's all there in his post.

“Friends, every day brings us more heaviness. It’s unbearable what’s happening. War is horrific.

A lot of people are demanding that the company climb up on an armored car [a reference to a famous Lenin speech] and loudly state its position. I think that any actions should be motivated not by emotional impulses, but by key priorities.

What I consider most important for us:

1. The safety of our employees.

2. Keeping our key services up and running.

What we’re defending now is not just a business. It’s services that are as necessary as electricity or the water supply. The search engine should search. The taxi should come. The goods and food should be delivered. The infrastructure should function.

For that reason, we can’t climb up on the armored car. I hope I explained the situation clearly enough.”(Khudaverdyan’s Facebook post from March 2, evidently in response to Lev’s appeal)

Since I was educated as a linguist, this is interesting for me. I want this to be a subject in school, especially in Russian schools. Have children take markers and find factual errors. Find lies.

Speaking — thanks to you — with journalists over the last week, I felt this strong professional satisfaction, even joy, in discussing interesting and important topics with well-prepared, intelligent, calm people. They listen. If they don’t understand something, they ask me to explain. And then they write about it in their own words.

When I speak with [New Yorker writer] Masha Gessen, on the next day I spend half an hour talking to a fact checker. It's just a whole different level. In Russia, in all these years, there was never anything like this.

Tigran is like Putin. Putin appears to be his model. He'll be very hurt if he finds out I said this. But this post about the armored car. What’s this joke about climbing on an armored car? It's funny to read about how the foreign press tried to translate it. Like, what the hell does this mean?

How would you translate it?

I don't know! It's a Lenin thing. It's a demeaning, joking way to refer to your opponent, in this case me. And then he ends his post: “I hope I explained clearly.” This is boorishness that he’s using to cover up the holes in his logic.

These rhetorical moves: Taxis should carry people, deliveries should deliver things. Man, you're like some kind of Mother Teresa! And people in the comments are saying, what about the news? Should the news be lying?

That’s the main narrative I heard, even when I was still working at Yandex. And this happens very often in Russian institutions: “We make compromises in order to save the company.”

“We need to think about our employees.” And in response I say: You guys have 18,000 employees. Highly-paid IT specialists. Super in-demand. You feel responsible for them, like they're children. But what about your tens of millions of users, from whom you're earning money? You don't feel responsible for them? Thirty million people a day who go on your site and use your news product. Do you have any responsibility there?

They positioned themselves as an international company, not groundlessly. They're listed on Nasdaq. But when they’re abroad they speak in one way, and in Russia they speak in a different way.

And when the whole world is looking at Russia, now international journalists have to translate expressions like “climbing on the armored car.”

We’ve seen how [Meta CEO Mark] Zuckerberg and [Google CEO] Sundar Pichai answer questions in front of a Senate commission. We hear the questions. Sometimes they say they don't know. But they don't say, you want me to climb on an armored car? They don't use stupid analogies.

Remember this story with [political consulting firm] Cambridge Analytica? When it turned out that Facebook was leaking data to them? And then it turned out you could use artificial intelligence [with that data] to tell every person what they want to hear.

And that, for me, was a story about how modern information technology entered politics. And everyone was horrified. But people didn't understand — and I didn't understand, it still has to be formulated — what’s so bad about this situation. This topic is still very interesting for me, and it's too bad I don't have a platform on which to discuss it.

But look at American society — these Senators' sometimes awkward questions — this is an amazing thing. People who are elected by regular citizens formulate questions, and voice fears, in their name. And they expect answers. And when they don't get them, they ask again. Or they issue fines. And the industry tries to answer. This painful, living process takes place, of formulating rules for a situation when technology has gotten ahead of society.

But in Russia, it's just stupid. In Russia, a super cool company with advanced technology is rebroadcasting 10 sources that are absolutely under government control. There's nothing like that anywhere else! No one suspected that it’s this blunt and this stupid. And this powerful.

When you're on the inside, you can explain everything. But I'm saying, look, guys, the end result is shit. And it doesn't matter how you get to that shit.

And really it was many separate decisions, each of which can be explained by itself.

Yes. And in general, even forgetting the politics, if you have a bad service, that's the main thing. If it's bad, you should make it good.

With this approach, you can't compete on the world market. You can compete on a non-competitive market, where you have advantages, where you're very big and you've crushed everyone else. But in the world, that doesn't work.

There are a lot of meaningful stories [in other tech companies]. About contracts with the Pentagon that were blocked from within by Google employees. Or this Dragonfly search, this project for China. Of course no corporation likes that. But if you’re comparing yourself to Google — do you have anything similar?

Within Yandex, it's like with Putin. Whoever is not with us is against us. They probably think this is normal. But it’s not normal. It's the opposite — some questions or unhappiness on the inside is normal. Of course it was very tempting to see Yandex as an oasis, but the further it went, the more it started to look, in its principles, like the government with which it worked so closely.

When things started to get worse, I said, sell this Russian part. Take the money and build an international business. This story about the headquarters — for half a billion dollars you can buy 100 companies. Good startups. You can buy 50. You can build a hub wherever you want, in Berlin or Israel or somewhere else.

But they built a business based on these couriers and taxi drivers. They built a business where it's tens of thousands of low-paid people who do hard physical labor. Google doesn't have that. Amazon does have that, but Google doesn't. That's their choice. So saying that they’re hostages isn't right. They had a choice, and a very good choice. It's bullshit. They fucked it up.

About the future — are they screwed?

I think they're screwed.

Along with the whole Russian economy?

In the first place, they're screwed along with the whole Russian economy.

In the second place, they're screwed because their international partners won't want to have anything to do with them. I’m not a specialist about big business, but I can read and make conclusions. I think in Russia they're screwed, it's easy to see why. But on the outside, it's because no one with advanced technology will want to work with them. Because they are dirtied by this war. And they should have accounted for these risks. And they didn't.

I think this is an important story because other companies that want to work in the West, they should know it won't fly. You can't be here, in Russia, helping an authoritarian regime grab a neighboring country, and be a high-end tech company in the rest of the world.

I have a last, wider question — you mentioned that your son went to Yerevan. What will happen with the Russian IT sector? They’re all leaving the country, right?

It’s not just IT people leaving. Everyone who can leave is leaving.

There are a lot of journalists in my circles, they left. It's clear that if I was physically in Moscow, now after this law… I don’t know. I don't want to go to prison. When I wrote my post, I wasn’t thinking about that. I was pleased with myself, how calmly I wrote it, how restrained I was. But the situation is changing very quickly.

About the IT people — of course, yes, they’re leaving. They’re in demand all over the world.

That's my question. Is this the end of the IT sector in Russia? That's my impression, that this brain drain is so severe that no one will be left.

Yes! It began earlier. There were a few waves. The Crimea wave. Then after the shot-down Boeing, people left. Then after the Moscow Duma elections. The Navalny wave. It's just that IT people, unlike my other acquaintances — teachers, journalists — they have no problems with the language. You just need a bit of crappy English. And they're in demand all over the world.

So, it began earlier. There are 150 former Yandex people in London. They work for Facebook or Microsoft. In Berlin there are some, I don't know how many, a lot. Now, of course, everyone is running. They're already running. They're like bakers. There's always a demand for them.

And even if Putin drops dead tomorrow and by some miracle this all ends, this sector is screwed in Russia, it seems like, for decades.

At a minimum. We all are. I have a neighbor here in Berlin, we're friends. Her parents were born in 1944. When they speak with me, they're still almost apologizing, at first.

For what?

Well, I'm a Jew from Russia. They have this feeling of guilt about the Holocaust and the war. Though it was just ending when they were born. So I have no doubts that, until the end of our lives, we’ll be explaining ourselves. We’re already doing it. And even my kids, they’ll be explaining themselves.

I have some responsibility too. But at least I left when it started to smell bad.

For that reason, you left?

To be exact: It was one of the reasons. The news service started changing. When something is wrong, you can leave a company. And you should. But I did participate in some compromises. In this filtration. I'm admitting that I had some responsibility. But over the last 10 years, they’ve been doing this without me.

I have one rule that crystallized for me: Everything should be public. There shouldn’t be any important things that you can't say publicly. You always need to be able to prove that your outlet is working in correspondence with your principles.

Let's leave Yandex alone for a moment. A search engine in China. It's not bad that you're working in China. If Google was operating in China but honestly said, guys, we have such and such demands from the government that we're fulfilling — that's better than lying.

If Tigran came out and said: “Our main page only allows these 12 sources, because that's what we agreed with the presidential administration, and otherwise they would close us.” That would be better than this shameful post about the armored car.

Maybe it's naive, but I believe that the worst thing is to lie. Lying is worse than stealing. If you steal, you can give it back. You can say you were wrong. But if you lie — you're compromised forever.

AS a journalist of many decades and having worked in Hong Kong for 10 years and seeing the crackdown on the media by Beijing I can quite understand Gershenzon's frustration, anger and hurt. What bothers me is that it is not only autocratic states and rulers who suppress free speech and journalism but also those who preach unendingly about freedom of expression in their own countries when their is creeping curbs on the media